An empire falls... and rises again. How "good" Russians from London see the future of Russia

Russia's new political exiles have adapted well to life outside of Russia. This conclusion can be drawn after attending the presentation of a new book by Russia's best-selling writer Boris Akunin (pseudonym of Grigory Chkhartishvili) on 9 May in London.

In Britain, there is no Putin, there is freedom, good earnings and Russian writers who continue to talk about the greatness of the Russian Empire and advocate for its renewed, civilised, but still empire. Only Ukrainians "spoil everything" for them.

"Please tell me how much money you donated to the Ukrainian Armed Forces and to whom? Who do you think needs more help now: Ukrainian refugees or Russian migrants?" I asked the writer at a meeting with readers in London, where he currently lives. Chkhartishvili was presenting the tenth volume of the History of the Russian State.

The room stood still for a minute and began to buzz with dissatisfaction, and a neighbour on the balcony pulled back and pushed my bag with her foot as if it were a Molotov cocktail.

The writer paused for a few seconds and replied that he had never donated to the Ukrainian Armed Forces because he could not destroy his own audience:

"I consider Russia's actions to be criminal, but I don't want to kill my compatriots, even if they are bad and wrong all around. It is beyond me".

In fact, this is the position for which Ukrainians use the phrase "good Russians" in quotation marks. They are against Putin and the war but not so much as to help Ukrainians destroy the occupiers. Not enough to want the collapse of the newest Russian empire, decolonisation and freedom for the people enslaved by the Russian government. They prefer to live in democratic European countries but often do not want democracy at home because they fear chaos and revolution.

Here, I recall the words of the host of another "good" Russian TV channel, Dozhd, who sympathised on air with Russians mobilised for the war in Ukraine, who suffered from a lack of food and uniforms. After that, Latvia banned Dozhd's broadcast, and the host was fired.

But Grigory Chkhartishvili seems to feel comfortable in the capital of the United Kingdom, and the audience at the London Geographical Society liked his answer. Akunin was given a standing ovation as an actor after the high note.

He said all his donations went to the True Russia Foundation, which "helped Ukrainians during the humanitarian catastrophe in 2022-2023." However, the foundation has been on pause since the autumn of 2023.

Russians talk about culture, Ukrainians collect donations

On 9 May, almost two hundred fans came to the presentation of Akunin's book. In the audience, I noticed Russian musician Boris Grebenshchikov and entrepreneur Yevgeny Chichvarkin. Most of the audience was flipping through a newly purchased copy of the tenth volume of the History of the Russian State (£40) in the foyer. Tickets cost from 25 to 150 pounds (150 included a reception after the presentation). The book, titled The Destruction and Resurrection of Empire, is dedicated to the Leninist-Stalinist era (1917-1953).

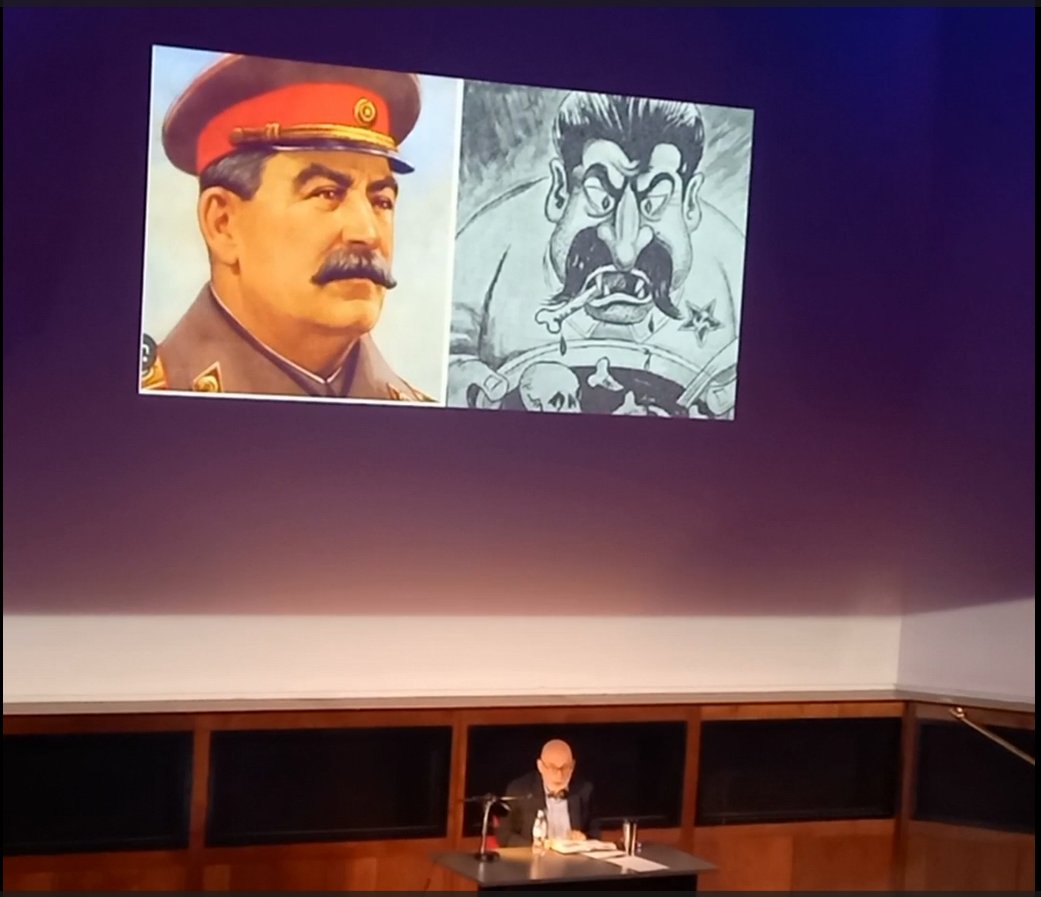

Speaking about the book, the author talks more about Stalin's achievements in building a "great state" than about the horrors of Stalin's terror.

The event was organised by Zima magazine, whose stall offered T-shirts with an absurd dialogue between the late opposition leaders Boris Nemtsov and Alexei Navalny, where Boris promises Lesha that all the headlines soon will be about Russia being free.

In the foyer, you could hear Russian, Belarusian, Kazakh and even Ukrainian.

People came with their families. "I brought my children, let them see what a great history we had," a blonde woman with bored teenagers in suits with the emblem of a private school said in Russian.

At the event, it was clear that this kind of public appearance was a tradition for a lot of people. Visitors discussed previous performances by Akunin and other Russian touring acts. In April, Navalny's ally Lyubov Sobol performed in London, now it's Akunin's presentation, the disgraced daughter of actor Vladimir Mashkov is due to perform in May, and actor Dmitry Nazarov is scheduled to perform.

UKRAINIAN CULTURAL EVENTS IN THE CAPITAL OF THE UNITED KINGDOM ARE LACKING

Ukrainian cultural events in the capital of Great Britain are lacking. One can only think of concerts or local fairs in the "Ukrainians for Ukrainians" format, where everyone brings and sells food and sends money to the Armed Forces.

Sadly, there are far fewer writers, philosophers, historians, and simply intelligent "talking heads" coming to Britain, and we are lagging far behind in promoting the Ukrainian vision of the same history.

It is not surprising that the history of Ukraine is still often presented in British children's books through the prism of the Russian vision (read more about this here).

On the one hand, few Ukrainians are published in the West and are familiar to Western readers, and on the other hand, according to the modern Ukrainian code of honour, men of a country at war, if they are not fighting, should stay quietly at home, not tour abroad. Even those who are legally entitled to do so are finding it difficult to obtain a travel permit. And Russians don't have to ask for permission to leave.

Ukrainian nannies

Akunin's compatriots did not seem frightened or confused by the white emigrants of 1917. No, most of them had arrived long before the outbreak of full-scale war. In the foyer, people shared details of already closed deals, showed photos from their holidays, invited each other to visit, and made small talk. The topic of Ukraine also came up but in the unexpected context of the cost of Ukrainian nannies.

"There are a lot of them, and they are ready to work for a pittance, but it's scary to let them work with children, they will teach you something, and they will speak with an accent," a young Russian mother, who looked like a child herself, warned her friend.

The event also attracted the attention of Western journalists. In particular, New York Times journalist Neil MacFarquhar and several Slavic studies students came.

"Why aren't they pouring to the Victory?" an elderly Akunin supporter asked the ticket controller, "Last time there was wine.

"There is nothing to celebrate yet," the organiser replied

An empire falls... and rises again

The audience came to check Akunin's watch, and the writer did not disappoint.

"I have started a new publishing life here, where the evil spell of the Russian authorities is no longer in force," the author boasted of his contracts with Western publishers and the fact that 35 million copies of his books have been sold in Russia.

He hoped to publish the story in Russia and almost agreed to a censored version, offering to print out the pages published on the website that had been banned by the authorities and paste them into the book.

The writer called the two years after the outbreak of the full-scale war in Ukraine an extremely fruitful creative period.

It should be noted that Boris Akunin has consistently criticised Putin's government, which is why he has been designated a foreign agent and terrorist accomplice. He predicts that the empire may collapse, and "the war will end in a way that no one will like."

But if you listen to his talks at the presentation about Russian statehood, the role of dictators in it, the future of Russia, and the way he speaks about democracy and what he sees as positive and negative scenarios for his country, you get the impression that Akunin is a loyal soldier of the empire.

In a recent collection of his historical stories, Lenin is presented as a "purposeful individual" and Stalin's historical contribution is "undeniable": yes, he was cruel, but he was an "effective manager" who knew how to accomplish his tasks and led the state to "greatness".

The words "greatness" and "empire" were often used in the writer's speech in a positive connotation. While he calls the democracy of the 1990s in Russia "wild and loose", and the subsequent establishment of a dictatorship an "inevitable" choice of the authorities to preserve a "united and indivisible" Russia.

During the book's presentation, Akunin noted Stalin's effectiveness in putting the country on a war footing before World War II. "If it were not for Stalin, the USSR would have been defeated," he said, justifying the Red Terror, repressions, and the Holodomor. He did not mention the American Lend-Lease, which provided the Union with endless resources.

There was much in common between the policies of colonialism and extermination pursued by Stalin and his contemporary Adolf Hitler. They are compared by the American historian Timothy Snyder in his book Bloodlands, which describes the Second World War and the bloody terror in the USSR, which killed millions of people. But it's hard to imagine any German writer or historian in a cosy London room discussing Hitler's role in German history in the same way. For some reason, Europeans are more loyal to Stalinism.

The writer, like many Russian historians, called the Holodomor not a planned genocide of Ukrainians, but an artificially created famine directed against the peasant class, since Russians and Kazakhs also suffered from it. Such an explanation of the Holodomor is a repetition of the Kremlin's official theses and a classic marker of Russian imperial thinking, although there is ample evidence of the Soviet government's genocidal policy towards Ukrainians, and the Holodomor is recognised as genocide not only in Ukraine but also in 30 countries around the world.

"Derussification" and aliens

During the presentation, the audience was interested in the author's predictions about the future collapse of the empire. According to Akunin, the modern Russian empire was restored with the outbreak of the Chechen war. And theoretically, it could collapse. He even showed a video of the Kremlin tower falling down, but the tower was quickly restored and raised.

Akunin does not believe in the victory of democracy in Russia, and in fact considers it a danger that will inevitably lead to chaos and shootings in parliament. Instead, he proposes a gentle "demosquitization": to agree on a new federal system in good faith, so that Chechnya and St. Petersburg live under different laws.

We can welcome this vision.

On the balcony where I sat, having bought the cheapest ticket to write this report, "demorussification" sounded like an "inquisition".

Akunin's speech did not contain any modern narratives of Russian propaganda, and he called the war against Ukraine a subjective factor and a dictator's mistake.

When the time came for questions and answers, I was surprised by a question from a girl from Ukraine. First, she thanked Akunin for his work in good Ukrainian, and then asked him how he would explain the essence of a woman to aliens. You would agree that this is a "relevant" question in the third year of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

At the end of the two-hour meeting, there was a queue for the author's autograph. Among the people leaving the hall, I recognised a woman with teenagers. She shared her impressions on the phone:

"It was a wonderful evening, but the Ukrainians ruined everything again with their questions."

Many of the audience left the hall and went to the nearby Berlin restaurant after the presentation.